Jair Bolsonaro’s ousting of the CEO of oil giant Petroleo Brasileiro SA Petrobras could signal greater political intervention in the Brazilian economy, a trend that will likely affect the perception of risk in the country, industry experts said.

On Feb. 22, shares of state-controlled Petrobras tumbled 21.7% as investors assimilated the news that the CEO of the largest oil company in the country would be promptly removed over a fuel hike feud. Then-CEO Roberto Castello Branco, who had plans to raise prices in tandem with global markets, had clashed with the executive branch in Brasilia, where the increases were regarded as an unpopular move.

On Feb. 19, Bolsonaro nominated Joaquim Silva e Luna, a former army general, to take over at Petrobras, one of Latin America’s biggest corporations. Investors reacted quickly to the news, resulting in an estimated market value loss of 100 billion reais for the company in a two-day period.

“The president’s decision to sack the CEO points to greater government intervention in the economy and could be a prelude to a looser fiscal stance,” William Jackson, chief emerging markets economist with Capital Economics, wrote in a note. “The country’s financial markets are likely to remain under pressure.”

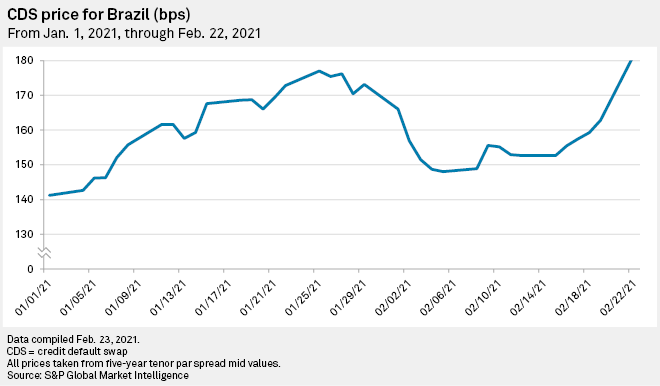

According to analysts, the effect of the decision will not be limited to Petrobras but is already being felt at large. 5-year CDS prices for Brazilian debt, a measure of credit risk, jumped to 183.35 on Feb. 22, up 11.9% from the previous trading day and up 28.45% year-to-date.

“The exchange rate and debt spreads are likely to suffer distress as it becomes clearer that the government is quite interventionist and not as liberal as many people believed it to be,” Fernando Ribeiro Leite, a professor and economist at the Sao Paulo-based Insper business school, told S&P Global Market Intelligence.

“This is not an isolated event,” he added. “The government and its military wing think they can do whatever they want with state-owned companies.”

Earlier this year, investors were baffled when local media reported that Bolsonaro had decided to remove the CEO of state-controlled Banco do Brasil SA, over the launch of a downsizing program a week earlier. Although Bolsonaro’s reported decision to oust the CEO — who had been in office for barely four months following a previous dismissal — was reverted at the last minute, the episode triggered governance risk alerts for analysts.

A pattern emerges

“Since the beginning of the year, several events have begun to indicate an increase in the risk of political interference in Brazilian companies, mainly in state-owned companies,” Fernando Ferreira, chief strategist and head of research with U.S.-listed XP Inc., said in a note to investors.

In January, the CEO of Eletrobras, the largest state-run company in Brazil’s electric sector, resigned citing personal reasons. A month earlier, the company chairman had resigned on similar grounds.

Following the sacking of Castello Branco at Petrobras, Bolsonaro told supporters that he was planning to “stick his finger in the electric energy sector, which is another problem,” doing little to allay concerns over interventionist policy.

Sergio Vale, a chief economist with Brazilian firm MB Associados, argued that the recent Petrobras decision opens the door to a sort of “tariff populism,” in which the government holds a tight grip on utility prices. “The view of Bolsonaro as a liberal was always misleading,” he said in an interview. “A lot of people in the market are dropping this illusion. His origins are not of a clear liberal conviction, but rather of an interventionist of the highest degree in his 27 years in Congress.”

In that light, there is a growing fear that interventionist measures might be extended to other sectors and areas of the economy. “It is very likely that we will witness a process for the next two years in which president Bolsonaro is exclusively focused on reelection,” Vale said. A survey of investors by XP released after the news reportedly showed that 57% of investors now think the government’s formal spending cap will be broken this year, up from 32% last month, Reuters reported.

“Meddling with prices is a turn toward populism that once and for all puts to rest the idea that this would be a liberal government,” Roberto Dumas Damas, an economist and professor Insper business school, said in an interview. “What will [Bolsonaro’s] speech be regarding the expected hike in the [Selic] interest rate? It ends up spreading fear. If [economy minister Paulo] Guedes already came out more or less debilitated, what could happen next with [Central Bank President] Roberto Campos Neto?”

Guedes, once the paladin of liberal policies in the Bolsonaro cabinet, has been gradually relegated from major economic decisions. The fact that the president seems to be calling the shots adds to the worries. “Guedes no longer has as much strength as he had in the past,” MB Associados’ Vale said. Otherwise, he stated, he would have prevented Castello Branco from stepping down.

Bolsonaro’s hasty call comes at a time when support for the government begins to wane. The latest poll by Datafolha shows approval ratings for the president dropped from 37% in December 2020 to 31% in January, close to its lowest reading of 29% in August 2019.

For some, however, political meddling with state-run companies is now harder to exercise than in previous administrations. Brazil’s securities industry watchdog CVM has reportedly begun an investigation on the decision to remove Castello Branco from Petrobras.

In a report sent to S&P Global Market Intelligence by UBS, analysts said that while there are notable risks, regulatory frameworks at the state-run company level are “very different” from what they were five to 10 years ago. “‘Haunts from the past’ are impacting investors’ perceptions,” Luiz Carvalho, an analyst with the bank, wrote.