In 2014, the state of São Paulo, one of Latin America’s most heavily urbanized areas, experienced a particular climate change effect. It suffered a historic drought that lasted for more than two years.

“We had to take short showers,” said Christopher Wells, Banco Santander SA’s global head of environmental and social risk. “It makes you think about life in a very different way.”

Brazilians had to cut back drastically on water consumption and some companies considered relocating during the crisis. Wells said the bank thought all of its clients would be impacted.

“So we decided to build a water shortage aspect into our credit risk models,” Wells said.

Banco Santander was one of the major Brazilian lenders to incorporate a sustainability rating into its traditional loan analysis. Borrowers with better water treatment, or located in an area with abundant supply, could benefit from a lower rate.

ESG financials: revisiting regulation

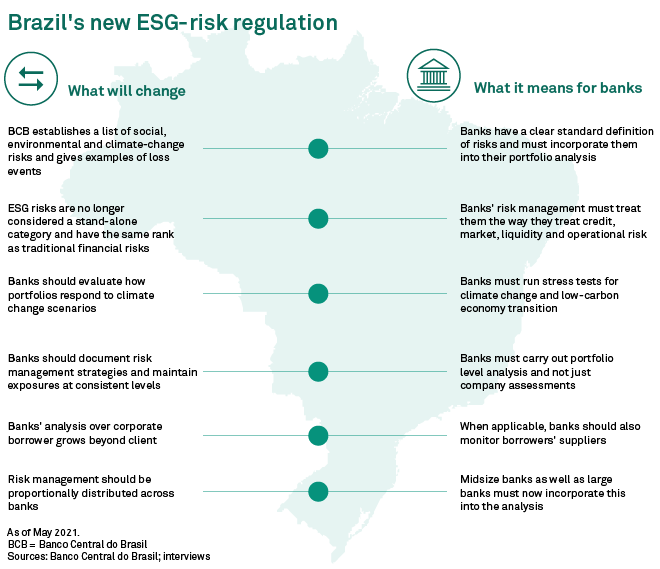

Seven years and one pandemic later, Brazil’s central bank is stepping up its environmental, social and governance, or ESG, framework. To do so, it is putting together a list of risks that banks will have to incorporate into their models. In order to manage those risks adequately, banks will be expected to come up with mitigation and response plans to compensate for losses. These may arise from events such as environmental fines, land contamination, natural disasters or excessive use of resources.

A first-round of regulation is scheduled for July, calling on large and midsize banks to scrutinize portfolios. In addition, they will also have to conduct sustainability-focused stress tests. Those will require ESG criteria to be fully merged into their credit models. A second and final round is expected in 2022, in which banks will need to pass or score with a certain grade.

The decision to revisit ESG regulation reinforces the view that the central bank sees the potential impact of these environmental risks on the system’s overall stability.

Covid effect

COVID-19 has only accelerated worldwide concerns on climate change. Banks now have to be particularly cautious of exposures to sectors that might be vulnerable to rising temperatures. Also, to effects associated with the transition toward a low-carbon economy. They must be wary of any climate change effect that might take place in the future.

“Banco Central do Brasil was a pioneer in 2014 when it launched rules on these topics,” said David Valente, division head at the central bank’s Regulation Department. “After seven years, we felt it was time to improve regulations.”

Valente explained that the upcoming prudential regulation would take into account potential climate and environmental risks. This is especially true for large projects that develop over a long period of time. From beachside resorts that might get swamped by rising sea levels to fossil-intensive energy companies that do not timely pivot to renewable sources, banks must now consider such criteria when evaluating credit risk for their clients.

What comes next in ESG regulation?

“What needs to be done now,” Santander’s Wells explains, “is [to] improve analysis at a portfolio level and not just company assessments. Are we exposed to a sector that could be impacted by climate change in a big way? That is one of the big questions banks have.”

Itaú, Brazil’s largest bank, is currently developing tools and methodology to incorporate climate factors into its risk models. The scarce availability of data and methodologies is one of the challenges in risk analysis, a spokesperson said.

Another layer of complexity, according to Itaú’s spokesperson, is working with the uncertainty inherent in the evaluation of multiple scenarios. There are different timeframes in which risks might or might not develop. On top of that, a particular climate change effect might not be as evident.

Climate change effect on portfolios

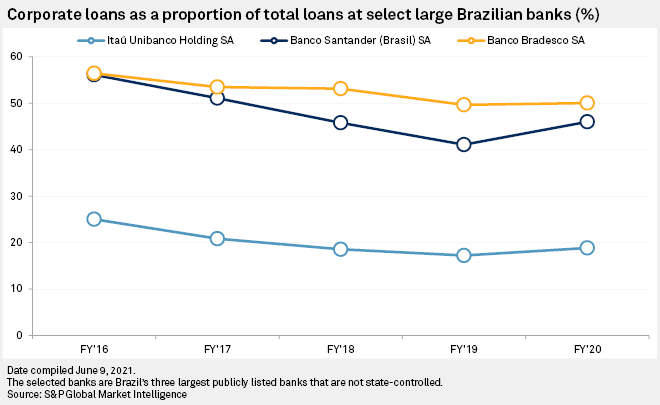

Corporate lending accounts for 18.8% of the total loans portfolio at major institutions. In every new disbursement, sustainability factors already feed the borrower’s risk analysis.

Santander Brasil, for example, scans about 2,000 companies with yearly sales of over 20 million reais. It assigns them a sustainability rating which is baked into their loan rates, especially for sectors that require environmental permits, Wells said.

The vast majority of those companies are located in the heavily urbanized state of São Paulo and in the Southeast of Brazil.

Contaminated land is an issue in the state of São Paulo. The city of São Paulo used to be an industrial cluster decades ago. Real estate land, which is typically put up as collateral, could require further scrutiny from an environmental standpoint.

Since the drought in 2014, water management has also become an increasingly important factor. “We created the system partly thinking of climate change but also because of real concrete considerations that we were seeing,” Wells said. “Because of the drought, a significant part of the rating is related to water.”

“Banks in Brazil, especially the most complex ones, already have self-regulation,” said Carolina Barbosa, an adviser with Banco Central do Brasil.

Climate change effect on agriculture and the Amazon rainforest

Brazil’s agribusiness sector, one of the largest recipients of corporate loans, has come under increased scrutiny. Ecologists and investors have challenged food companies for using deforested Amazon land to grow cattle or soy. For banks, assessing environmental risk means going beyond direct clients, and into their customer’s suppliers as well.

“OK, so the factory might be fine. But they do buy soy, sugar cane, or beef. Now, what are they doing in terms of their suppliers?” Wells said. All those things add up into their credit rating.”

Although loans to the Amazon region amount to less than 5% of banking portfolios, the region demands great attention from bankers. Despite the low share that these loans represent in their portfolios, banks dedicate considerable care and attention to any reputational damage risks.

“We devote 30% of our time on Amazon-related issues,” Wells said. Santander looks at ranchers and farms. It double-checks whether the bank might be lending to a farm that could be encroaching into land of indigenous communities or that has been deforested illegally.

Robust official data allows banks to trace back supply chains effectively. But records on environmental matters are not as abundant. When it comes to greenhouse gas emissions, banks are dependent on what clients report in their inventories. “And when they do not, we need to estimate emissions based on financial data,” the Itaú spokesperson said..

ESG financial risk grows

Social issues also have the potential to disrupt companies, central bank officials said in interviews. Less than a year ago, the violent death of a black man at the hands of Carrefour security guards in Porto Alegre sparked social protests. Protesters attacked the supermarket’s branches in different parts of the country and the company faced widespread condemnation.

Another recent example of an unexpected human and environmental disaster was the 2019 collapse of the tailings dam at the Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine in Brumadinho. The resulting mudflow took the lives of an estimated 270 people and agricultural lands were contaminated. The companies involved had to respond financially with sizeable fines.

Mining giant Vale inked a settlement in February for a payment of about $7.02 billion to the Minas Gerais state. It was made to compensate families of those who died in what is considered one of the worst environmental tragedies in Brazil’s history. Groups representing the victims, however, later challenged the terms of the settlement.

“Banks must be aware that these risks may materialize,” the central bank’s Valente said. “They will now have a very clear definition of what those risks are and what loan loss events could be associated with each of them.”