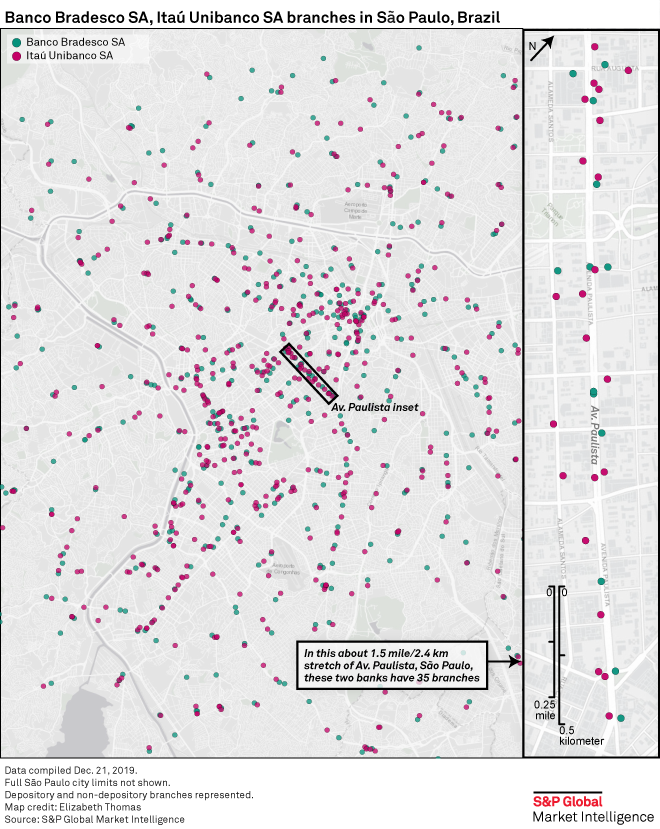

Avenida Paulista is a top tourist attraction in São Paulo, Brazil, with shops, restaurants, cultural and music venues lining the 2.7-kilometer road. It is also one of the country’s most over-branched areas.

Over the years, retail banks have added a slew of branches along the avenue. Banco Bradesco SA and Itaú Unibanco Holding SA — Brazil’s the two biggest private banks — have as many as 35 branches between them along the strip, mapping data from S&P Global Market Intelligence shows.

But Avenida Paulista isn’t alone. Brazil’s entire Southeast, of which São Paulo is a part, has more branches by area than anywhere else in the country.

“You can have two or even three branches of the same bank in a single block,” Luis Santa Creu, a São Paulo-based bank analyst with local firm Austin Ratings, said in an interview. “It’s absurd.”

Industry experts say that the costs associated with maintaining those branches already has started to impact profits. According to a recent report from German consultancy firm Roland Berger, the top 5 banks in the country will need to cut expenses by 24 billion reais in the next three years to remain competitive. Much of those cuts will have to come from branch reductions “In Brazil, you are over-branched,” Antonio Bernardo, managing partner in Latin America at Roland Berger, noted in an interview.

Fierce fintech competition and declining interest rates are rapidly pushing heavyweight lenders to scale back their physical footprint, as they increasingly go after digitally savvy customers in highly concentrated urban areas.

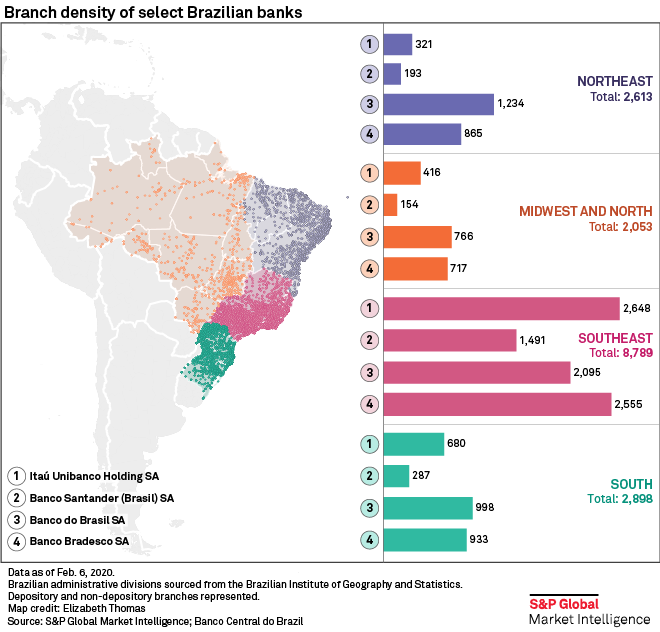

The top 4 lenders had 16,353 brick and mortar branches as of late 2019, 8,789 — or 53.75% — of which are located in the highly populated Southeast region. There, Itaú and Bradesco have more than 2,500 locations each.

Private lenders scale back

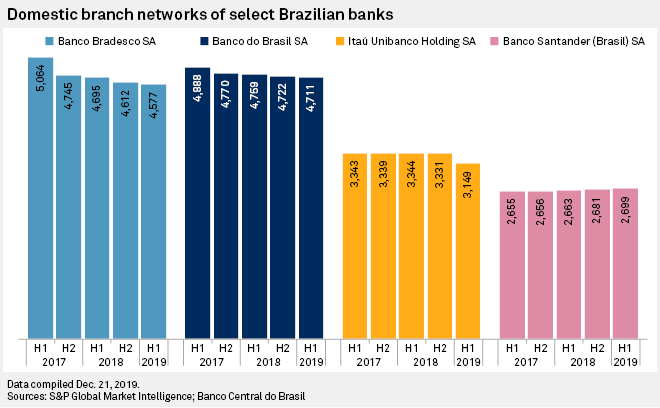

Private banks already have begun to thin their branch presence in recent years. Itaú and Bradesco shuttered a combined 511 branches in 2019 alone, and both have signaled that more closings are on the way.

Decisions to reduce brick and mortar outlets are frequently accompanied by severance programs. Even state-controlled entities like Caixa Econômica Federal and Banco do Brasil SA are now reportedly looking to follow suit.

Among publicly traded banks, only Banco Santander Brasil SA continued to add branches in Brazil; though it’s total branch count, at 2,699 locations, continues to be a fraction of its larger peers.

“It was very naive to think that the bank would just sit and do nothing,” Sergio Furio, CEO of fintech Creditas Soluções Financeiras Ltda., said in an interview. “The productivity of a bank branch in Brazil is very low … [and] the necessity of that [physical] channel is diminishing,” he said.

Bradesco said it plans to shut down 300 more branches in 2020. Itaú, which culled 10% of its branch footprint in 2019, has not disclosed how many more closures it is targeting, but it confirmed it will proceed with a “multiyear efficiency effort” to reduce its branch network.

“We still have not decided how many,” CEO Candido Bracher said on Feb. 11.

But while the branch reductions have been notable, some analysts argue that they are not moving quickly enough. According to Roland Berger’s Bernardo, banks still have yet adequately address the issue. “They need to go further [into] a stronger wave of efficiency,” he said.

‘A foot in each canoe’

Part of the hesitation in closing branches more aggressively, Austin Ratings’ Santa Creu noted, is the struggle in converting clients to digital channels everywhere.

“It’s not yet a brutal closure, banks still want to have a foot in each canoe,” Santa Creu said. “There are remote areas in Brazil where a branch is still necessary.”

Private banks have a more robust presence in the more affluent south and southeastern regions, while public institutions’ footprints are generally more spread out. State-controlled Banco do Brasil has a leading presence in the midwestern and northern parts of the country, as well as in the northeast. That geographic spread, it argues, is key to securing financial access in small towns.

Assessments of the bank’s network are “permanent,” a spokesman from Banco do Brasil told S&P Global Market Intelligence. Getting it right, he argued, can boost efficiency levels.

Banks base their branch decisions heavily on transaction volume, client base and the location’s capacity to generate new businesses. Some are shut down, while others are scaled down to offer fewer services or transformed into a digital outposts where clients can access their accounts.

As digitization sets in and the effects of open banking and fintech begin to be be more fully felt, analysts say that banks will have to continually assess branch mixes.

It is a process of trial and error, and with that, “there will be winners and losers,” Creditas’ Furio said.

As of Feb. 19, US$1 was equivalent to 4.37 Brazilian reais.