Shortly after primary election results catapulted Peronist presidential candidate Alberto Fernández to front-runner status, he promised bondholders that his government would not default on its debt, unlike prior administrations in his party.

Bond markets don’t appear to be buying it.

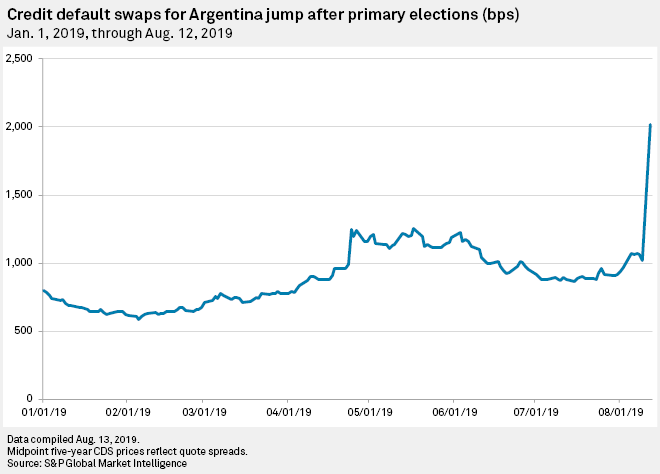

In the wake of the surprise primary result, investors halved the value of an array of Argentine assets, and country risk skyrocketed to a 10-year high. Argentine debt is now trading at about 50 cents to the dollar, pushing yields on bonds maturing in 2020 above 60.0%.

Analysts say that pricing reflects a high probability of a sovereign default.

“It looks inevitable,” Balanz Capital’s Ezequiel Zambaglione wrote in a note to investors. The firm estimates that current pricing suggests an 80% to 90% likelihood of some kind of restructuring event that will result in bondholders taking a 45% to 55% haircut.

“In the last 48 hours, it was clear that political uncertainty does a lot of damage,” President Mauricio Macri, who trailed Fernández by 15.5 points in the primary vote, said Aug. 14 as he announced new initiatives in an effort to stem the turmoil.

The biggest surprise of the primary for markets may well be that its result was meaningful at all. Argentine primary elections have typically only served to weed out longer-shot candidates from the general election, and results are often highly fragmented. But with a small number of competitive candidates, Fernández managed to win more than 47% of the vote, higher than the 45% needed to clinch the presidency in the first-round election on Oct. 27.

The sudden ascent of Fernández as Argentina’s presumptive next president comes as he has yet to lay out any concrete economic policy plans, leaving markets with little insight into how his administration may govern. This uncertainty is exacerbated by his vice presidential running mate, Cristina Kirchner, the former Argentine president whose term was dominated by protectionist policies and included Argentina moving into selective default after it missed payments on some of its foreign debt. Roughly 78% of Argentine debt is denominated in foreign currency.

“Fernandez is making an effort to appear moderate and reasonable, but he does have a Kirchnerist team surrounding him,” Santiago Gallo, a financial institutions director with Fitch Ratings, told S&P Global Market Intelligence. “We do not know what vision (of the economy) will predominate.”

That uncertainty has born down hard on Argentine assets. The Argentine peso has lost 22.4% of its value in recent days, while the benchmark Merval stock index has fallen 31.6%.

“The issue with Argentina is that political swings are very pronounced,” Fernando Díaz, a New York-based economist with Citi, told Market Intelligence. “What the market is going to ask for is a more complete and detailed government plan.”

It is still unclear when Fernández will present his plan, or what it will look like. But the election result “implicitly denotes population demands for reorienting economic policies once the new government assumes power,” Gabriel Torres, a senior credit officer with Moody’s, said.

In the meantime, Argentina is caught in an unusual political circumstance: the primaries have given it a presumptive presidential winner, but the result legally means nothing.

“You have high certainty of who is going to win the elections, but institutionally Fernández is still just one more option among candidates,” Citi’s Díaz noted. “That makes it difficult to think of an orderly transition. [This] institutional void will prolong uncertainty in an economy which is already showing a high level of volatility.”

It is a situation Fernández himself recognized in a recent television interview: “What can I do? I’m just a candidate, my pen doesn’t sign decrees,” he said.

As of Aug. 13, US$1 was equivalent to 55.25 Argentine pesos.